cover for the Kindle edition

I will never be satisfied with my first novel, The Elephant of Surprise. (First? Read on.) The book is didactic in parts. It lacks humor. The pacing is awkward. There are parts of the story that I don’t like. I’m annoyed by most of the characters, especially by the male lead, Andy. He’s naïve and lacks vitality. (He resembles me too much.) However, after completing what I believed at the time was a worthy novel (written between 1972 and 1982) I attempted to entice several publishers to consider it. All declined even to look at a sample.

The original typewritten copy no longer exists — perhaps that is the one I sent to the Library of Congress in 1982 to secure a certificate of copyright. Two photocopies remain, double-spaced on 350 pages. These I shoved into a box and relegated to basement storage in 1983, there to repose for the next 40 years.

In that time I went on to write seven more books which have all been published. And during the intervening years I would occasionally think back on that first, unpublished work and reflect on some of its features. I dismissed it as a fun exercise, good for practice, but not up to my later standards in storytelling, language, and character development.

Still, some of the motifs in that first novel had stayed with me and, in 2019, as I was writing my third novel, Cold Morning Shadow, I carried a few of those ideas over, not expecting that I would ever resurrect my first “practice” manuscript. Someone who has read Cold Morning Shadow and then later reads The Elephant of Surprise (or vice versa) will notice the resemblances. I repeated these elements in the later novel, wishing not to relegate them to oblivion.

One day in 2023 I happened upon those stored copies of my first novel. When I leafed through the pages I found myself thinking: There’s some good stuff in here.

Almost committed a grave error

There was also something in it that could have been disastrous had it been published long ago. The story I had created included a night scene involving a young couple not yet fully at ease with one another. One of the pair, intending to apply a band-aid in the dark, discovers that a faint light is given off between the two halves of the wrapper as it is being peeled open. In the scene I wrote, this discovery leads to a romantic frolic in which the two tentative lovers cover one another with plastic bandages. That provided a crucial turning point in their relationship. I thought it was clever.

By chance, not long after I began searching for a publisher, I read the book, The Milagro Beanfield War, by John Nichols. I liked it, and so I picked up another of his novels, The Sterile Cuckoo. In that one I found a scene involving band-aids almost-identical to the one I wrote. I was crushed. Any writer of fiction risks such a coincidence, and there is no way to be certain that some fragment of a story has not been used before.

How the novel began

At 21, in the spring of 1972, after a year of college, I arrived for the first time in Europe as a soldier in the U.S. Army participating in the occupation of Germany about a quarter century after the defeat of the Axis powers in World War II.

I wanted to write; not to be a “writer” but more specifically to express myself in words as other artists express themselves in media as diverse as food, music, photography, architecture, and painting. As early as junior high school I had discovered the therapeutic effects in creating fiction. By then I had come to realize that fiction not only entertains but can enlighten. I looked forward to writing assignments in school and often composed far more than was requested.

(I have destroyed most of the examples of those efforts, which I later excavated from a childhood stash and which were not already consumed in a structure fire. What remained might have been good work for a 14-year-old but I didn’t want them showing up in a posthumous collection of early writings.)

I practiced my wordcraft through high school, aimng for humor with realism and striving for linguistic precision. It was important from the beginning that nothing I might write be misunderstood or tossed aside because it was boring, confusing, or incomprehensible. Therefore grammar and structure mattered to me, and I took care in crafting and editing my work.

One May day soon after I had settled in Augsburg, Deutschland (West Germany), I took myself into a field outside the Army base, a spiral-bound notebook and pencil in hand. With the seed of a story in mind, I began what I hoped would, and did, become a novel. More than 50 years later I can relive the exhilaration and anticipation I felt in writing those first words, taking those first steps.

I had only a vague theme for it, no specific setting, and no plot except that it would be a love story with a twist. (A romance is a plot in itself.) One of my younger sisters, while in her teens, had become an accomplished painter in tempura and acrylics and was a passionate romantic. She would inhabit the story I was about to write.

How it progressed

A couple of notebooks later, after spending a year and a half traipsing the countries surrounding the Alps, I returned to the States to resume my pursuit of a college degree. The novel at this point, if compared to a painting, consisted of a few scattered splotches on a wider canvas, each a scene vividly assembled of many words. Like memories, the events I had concocted made sense and were connected but I had not expressed any of it in ways that others could follow. For memories, although easily reamalgamated, are difficult to convey to others.

Two years after I began the novel — still a work in progress — I was engaged to be married. So now there was another young woman, dark-haired and blue-eyed, incisive and quick-witted, who would be represented by one of the fictional characters. The novel would not lift events from their lives but would lift real people such as my sister and my fiancée and portray them in the story’s events.

For the next eight years after returning from Europe, by this time a newly-married man passing into fatherhood, I patched the vignettes of my fictitious story into a contiguous piece of literature. I called it Nalbandian, which was the name on a business I had seen somewhere. (I didn’t realize that that was in fact someone’s surname.)

A second novel, and trying to get them published

In 1982 I registered the manuscript for a copyright, a procedure that is not necessary in order to secure a copyright but does add a level of certainty to its authorship. Over the next five years or so I trolled it before publishers in the naïve hope that one would make an offer on it. None did, and of that I am now glad. I know that every version of advice-for-authors includes the caveats: Write what you know, and write your own books, not what you think someone else wants to read.

In the intervening 40 years I attended to earning a living in manufacturing and in health care administration while raising my own and other people’s children. In 1989, seven years after parking that first novel, I took up my pen once again and began another — much different than the first. Seven years after starting it I had a draft of Fire, Wind & Yesterday, which I again trolled before the mighty publishers of the day. Things were changing in that business, though. U.S. publishers were no longer themselves soliciting or accepting manuscripts and proposals. They now surround themselves with a cordon of literary agents, each working for an agency apart from the publishers, intervening to spare the printers the nuisance of selecting works worthy of publication.

in the 1990s, instead of reaching out to publishers as I had in the 1980s, I submitted my new novel to many agencies and followed whichever procedure each required — cover letter with sample chapters, on-line form with synopses, entire manuscript in specified format. I could not find an agent interested in literature, only those seeking stories that followed specific trends. All are strict about a word limit of 100,000. No agent asked to see the manuscript and none even acknowledged reading the sample material. The few polite enough to reply at all said that it it didn’t fit within the scope of what they were currently soliciting.

(Along about 2000 I read one of Jimmy Carter’s books — I believe it was Sources of Strength — and I wrote to him to ask whether he might suggest an agent since Fire, Wind & Yesterday was also, for me, a declaration of faith. To my surprise he returned my letter with a handwritten note at the top with the name of his own agent and wishing me the best. I then wrote to her, mentioned that former President Carter had recommended her, and included a sample of the book. She wrote back that… it didn’t fit within the scope of the works she represented.)

Literary agencies nowadays also feel the pressure to promote certain themes that conform to the agenda of social and political collectivism. And agents themselves are too young to evaluate fiction or non-fiction that takes place before the era of their own experience — chiefly the present century.

The vanity publishers

I must say that, if today’s standards had been in force in other epochs, we would never have seen the works of Dickens or Dostoevsky, Michener or Roberts, not to mention Shakespeare or even the Bible. Those whom I call the vanity publishers of today — so vain in their competition to ingratiate themselves to the dictators of social fashion that they shun literature in favor of banality — have as their objectives 1) to find those trite volumes written to formulae which the publishers’ algorithms predict will assure the greatest monetary profits, and 2) to satisfy what they perceive to be a market demand for fiction that grovels before the indignant masterminds of contemporary social ukase.

These are the sanctimonious publishing houses whose vanity suppresses worthy literature today, who, in the past century, coined the term, vanity press, for authors who, having objectives not in line with the oligarchs of established publishing conformity, reverted to self-publishing. It took me several years to understand this. It’s not that my writing isn’t worthy, isn’t entertaining and enlightening, isn’t literature. My writing isn’t socially progressive, nightmarish, or futuristic enough for commercial success, and isn’t sufficiently depraved for today’s readers, according to the industry.

I’m honored by that. I’m aware, too, that some works of fiction and non-fiction which do deserve to reach a wide market do manage to slip through the barricade. We know, too, that many are the smaller publishers dedicated to very specific fields of interest: children, gardening, model railroading, woodworking, athletics, religious denominations, and all the rest. Although not all of these publishing houses are looking for adult-level novels, each of the specialty houses is more open to an author’s idiosyncrasies.

DamnYankee Publishing

Fortunately in the USA we have the first amendment to the Constitution, guaranteeing that no one needs a license to publish whatever they want to in any way they want to, so long as one avoids libel. In 1999, after dangling Fire, Wind & Yesterday before the gatekeepers of the industry, I decided to make an end run around the self-important vanity publishers and started Damn Yankee Publishing at DamnYankee.com, ( URL that had not yet been registered by anyone else).

I had been writing short stories, and in that same calendar year I met over a dozen additional short-story writers in a little on-line forum. I solicited and edited one or more stories from each of that group, gathered them into an anthology, and published what was, to my knowledge, the first book ever released simultaneously as an ebook and in print, Three Naked Ladies Playing Cellos. (The title was not my own; two of the women involved provided the title, the cover illustration, and the poem based on the title.) That book is no longer in print, and to re-publish it might be more difficult than it should be since I’ve lost touch with the other authors and to distribute proceeds from a new edition could prove exceedingly difficult.

DamnYankee also soon published a couple of other works in digital format only. It was and has evermore been, however, a one-man enterprise. In 2000 my personal life was at its peak of complexity. I changed careers, we sold our house and bought one in a different town, we had a ten-year-old son with severe physical and developmental disabilities, we had two disabled foster children and three more long-term foster children in and out as well, and our two oldest children were in college. I had written an outdoor-oriented column for the Katahdin Times, was still writing longer pieces, much of it in the form of non-fiction articles. One of those was my own memoir of 23 years spent at Great Northern Paper Company, which was published in 2005 across two issued of a magazine, Bangor Metro, and which earned some widespread praise including a personal phone call from our U.S. senator, Angus King, and more of my work was to come. I was also continually updating and refining DamnYankee.com.

At DamnYankee.com I considered soliciting works by other authors which I might edit and publish, but I could envision with dread the amount of reading I would need to do merely to decide whether a piece was worthy of further effort on my part, and so I banished the idea. I added short stories of my own in free-of-charge digital formats, articles I had written on topics that stirred my passions, and links to additional ideas that deserved wider attention.

In 2012, sparked by an idea that I easily could have dismissed, I dashed off an ebook I called Babie Nayms. It was as whimsical as its title suggests and I do not take it seriously. It was merely for fun. About that same time I spent a few short weeks and created a juvenile novella, The Clover Street News. These were both offered in digital editions at Damn Yankee Publishing.

Using Amazon for printing, marketing, and distribution

In 2013 I was able to retire from one career and wind down in another. Still working seasonally as a Registered Maine Guide, which had been an avocation, I dug out Fire, Wind & Yesterday and rewrote it while converting it to a digital format that could be adapted for Amazon.com. At last, in 2017, that novel appeared in print-on-paper (old fashioned book with real pages) and for Kindle.

I quickly brought out Babie Nayms and The Clover Street News for Kindle and in paperback and Kindle editions and then, in 2019, began yet another novel. I completed it in a year: Cold Morning Shadow. But I was too hasty in publishing it. It is lengthy — a two-book saga in one volume, and, pinched by the onset of the covid pandemic, I took insufficient care in editing it before distributing sample copies in print form (beta copies or author proofs, whichever you prefer). By now, though, I’ve re-read it a dozen times, have included corrections from friends who were willing and dedicated proofreaders, and am persuaded that it is free of typos. I consider it worthy.

In 2022, prompted by a Christmas gift from our daughters, I spent six months composing a memoir of my first 23 years of life up to the time I met Beth, who has now been my companion since 1974 and my wife since 1975. This memoir exists now in a printed edition through Storyworth and in an on-line (not Kindle) edition at a personal web site under the title, I Shall Pass This Way But Once.

Among the articles that I had been publishing on line were several concerning my recent ancestors and other relatives. These I had been writing one at a time as I was excavating the content in boxes of documents left to me by my parents during their later years. In 2023 I collected and edited these pieces, added more elements, and in September, 2023, I published the book, Relics, intended more for my own relatives than a wide public audience. It has in a short time, however, reached quite a number of people outside the family.

Completing the Elephant of Surprise

In October, 2023, as mentioned earlier, I dusted off my 1982 typewritten copy of Nalbandian. I hadn’t turned its pages in over 40 years. And yet, as I leafed through it and glanced at the paragraphs, many lines of dialog hailed me from the pages and many scenes snapped back into sharp focus. Over the course of a few evenings I made optical scans of the typewritten sheets and, lacking a program for optical character recognition, converted it to a crude digital version of the 41-year-old printed text.

I am glad it was not published in 1982, although had it been, it would have stood as a contemporary novel at the time. Set in the 1970s and finished after I had spent only a few years working in Bangor and in Millinocket, Maine, it includes elements of my experience in those work settings as well as in the Army and earlier.

I wrote about what I knew then. Over the decades since, as my writing improved and as Nalbandian languished for lack of attention, I continued to insist that it was good for practice but nothing more. Now, looking at it more closely, I see some truly good elements in it.

I was a single man and “available” as I was first drafting it, although I had as little practical experience with young women as the male lead in the story. Romance and fascination with someone you’re attracted to is at the core of all human interaction, an enduring subject for fiction.

Therefore I decided to resurrect it and turn it over to the world. Perhaps it has the charm of innocence in the art of storytelling. For instance, there are too many characters. It has lurches in its time elements and, as originally written, serious omissions in development. These I have attempted to overcome as best I can.

It’s not perfect. But I believe it will entertain and will accurately represent its time and locales.

Editing it through the winter of 2023-2024 I answered the need to re-title it. The name, Nalbandian, rings with mystery but is too forgettable. The surprise features were in it from the start and we had used the phrase, the elephant of surprise, again and again in my family, so that seemed a good candidate for a title. It is now published 50 years beyond its conception and can serve as history. The places, some of which have been renamed for fiction, were real, and many of the incidents that serve as backdrops for the story did happen nearly if not exactly as described. Only someone as old as I am, who was there at the time, would be able to confirm or protest the authenticity of an event or setting.

What’s in the book

But it matters not whether some things truly happened and others didn’t. The story line is fiction through and through. The characters (all but one) are contrived, no matter how closely they resemble the people I knew who inadvertently served as models. My sister was the model for a girl who only marginally resembles her. Another resembles my wife. Some events are included exactly as they happened but with another character, not me, in the scene. (The account of Carol Sanders — her real name, though, is entirely true and factual, drawn from police records and from my own experience as her friend and my experience with the police at that time. In The Elephant of Surprise I merely substituted the character, Andy, for myself. Carol deserves to be remembered by more than a tombstone.) And the book is full of characters who never in my experience truly existed.

I wrote myself into several of the male characters. One is the man I thought I was right after I came home from the Army. Another represents the clumsy, inept, sometimes deluded side of me that I’m glad few people have ever noticed (I hope). Another is the man I might have wished to be. And others among the population in the book are nothing like me. The female characters are similarly a mix of people I knew, wish I knew, or am glad I didn’t.

I could have tossed out the original story and recreated the novel from scratch, although I didn’t. It’s another version of the same old romance that has been told, must be retold, and will be happily read in uncountable variations until the end of time — the story that, somewhere between adolescence and adulthood, a boy and a girl are attracted to each other. They do the “dance” that fits their generation, the structure of their culture, and the courage or reticence that each one has in meeting another person. One approaches the other, the other notices or doesn’t, they risk a little embarrassment and talk, spend time together, think, and then they spin apart. Each one then does the same with someone else. In time the original two come into view of each other, perhaps deliberately perhaps not, and interact once more. Or they almost do. And so it goes.

That’s what happens all through The Elephant of Surprise. Each member of the cast has features that set her or him apart from others, features that attract and repel. Each one is more (or less) experienced, caring, observant, patient, healthy, jolted, or jilted, than another.

Eventually or perhaps not, predictably or perhaps not, two of the characters whose heads occasionally bob above the undulating surface of the tale clutch each other in a lasting embrace. On the way toward this triumph or letdown, (however the reader perceives it), some surprises occur in the lives of the participants. Maybe the reader anticipates some of those surprises, maybe not.

So who are the players?

In approximate order of appearance:

Darryl and his cousins, Heidi and Charlie, venture woodward to go fishing. They all return but not unscathed.

Andy has served in the Army and returns to Maine to work his way through college. He befriends Darryl.

Andy had an important friend overseas whose name was Danny. Danny has a big influence on Andy. Andy’s not the only one who knows Danny.

Jack and Andy become acquainted and decide to pursue girls in different ways. Aimee is one whom they pay attention to.

The Octagon, an old-fashioned filling station/truck stop, is an important place in the story. So is a place called Pechera — not a town but a location.

Like Andy, Aimee is working her way through college.

Kenise and Andy are lab partners.

Andy works part of the time at the truck stop and part of the time in a mill where paper is made.

Joe is a big man who has a big influence. Jeanie sketches him without his knowing it. Andy catches Jeanie in the act. He learns that Jeanie has sketched him as well.

Irene is Jeanie’s friend. One day she meets Andy. Besides the cousins mentioned initially, other pairs of characters are related.

Additional characters come and go, and mostly they are clearly in supporting roles. Mostly.

There are important things that a few cast members, although acquainted, don’t know about each other. These pieces of information lead to… some surprises. There are clues in the story, but probably not enough to give it all away.

In the end, a couple of characters still might not know everything that the reader knows about them. Some day though, after the end of the novel, those characters will be greeted by those unsuspected surprises.

This is all that I will tell you about The Elephant of Surprise.

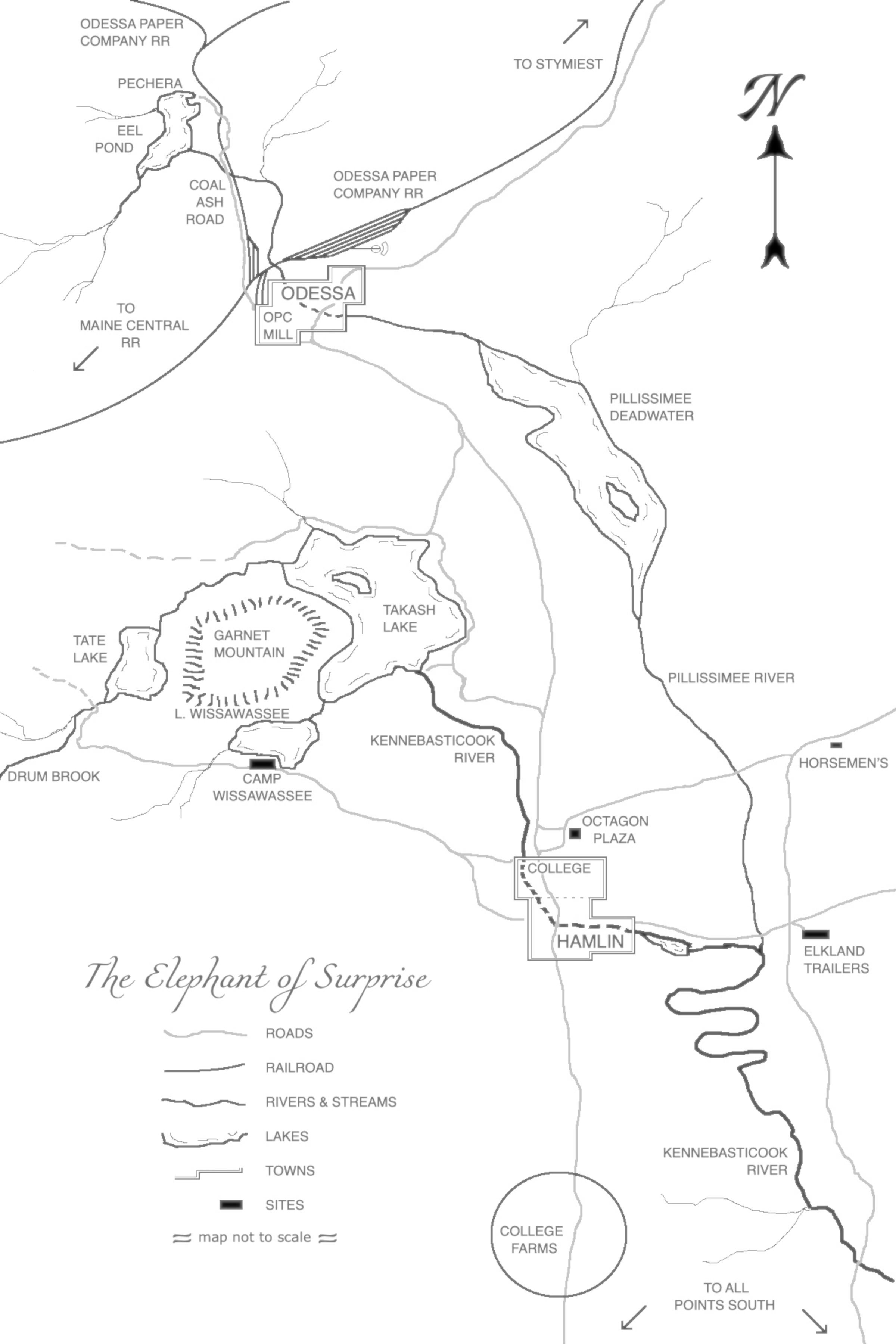

Oh, and here is a map for the setting where most of the book takes place.